How to Manage Oak Forests for Acorn Production

Paul S. Johnson, Principal Silivlculturist

Taken from Technical Brief, March 1994, USDA Forest Service

Importance of Acorns

Oak forests are life support systems for the many animals that live in them. Acorns, a staple product of oak forests, are eaten by many species of birds and mammals including deer, bear, squirrels, mice, rabbits, foxes, raccoons, grackles, turkey, grouse, quail, blue joys, woodpeckers, and water-fowl. The population and health of wildlife often rise and fall with the cyclic production of acorns. Acorns’ importance to wildlife is related to several factors including their widespread occurrence, palatability, nutrition, and availability during the critical fall and winter period. It would seem natural, then, that some oak stands and perhaps extensive forests be managed primarily for acorn production. Even though our knowledge of acorn production is incomplete, we have enough information to make reasoned decisions on the management of oak stands for acorn production.

What We Know About Acorn Production

Acorns of trees in the white oak group (subgenus Lepidobalanus) mature in 3 months; those in the red oak group (subgenus Erythrobalanus) require 15 months (two growing seasons]. However, in both species groups, acorn production is relatively unpredictable from year to year. On average, most species produce a good crop of acorns one year in three or four. In years of low or moderate acorn production, most acorns are consumed by insects. Moreover, the production of acorns differs among species. Some species are inherently better acorn producers than others, and different species tend to produce good acorn crops in different years. Although environmental factors unfavorable to acorn production such as late spring frost and summer drought tend to obscure inherent periodicity (cycles) in production, new evidence suggests that such periodicity occurs at 2-, 3-, and 4-year intervals for black, white, and northern red oaks, respectively.

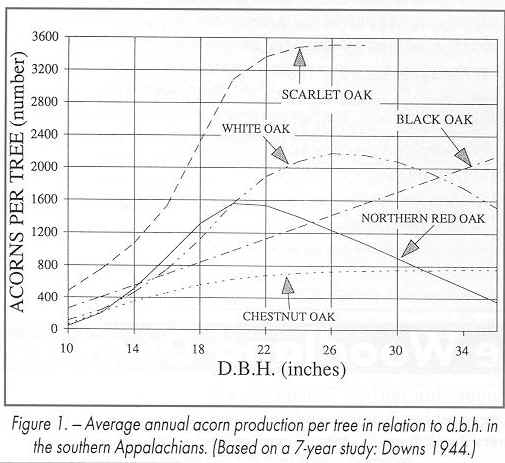

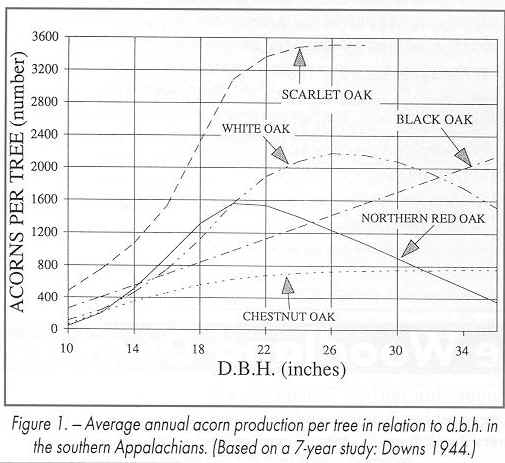

Other factors being equal, trees of large diameter produce more acorns than trees of small diameter. However, in some species, production declines after the tree reaches a threshold diameter (fig. 1). Oaks with crowns fully exposed to light, such as dominant and co-dominant trees, produce more acorns than trees with crowns totally or partially shaded. In the white oak group, when one tree produces well, all of the potential acorn-producing trees in the population tend to produce well. In contrast, in the red oak group, some producers yield well in a given year while others do not. In addition, only a relatively small proportion of trees are inherently good seed

For example, among white oaks in Pennsylvania, only 30 percent of large, healthy trees produced any acorns even in good seed years and an even smaller proportion produced a good crop in those years.

Management Methods

Substantial gains in acorn production of established stands may be obtained by following these guidelines:

1. Before the first thinning, identify and reserve the good acorn producers in each stand. To do this, you'll need to observe and keep records for 5 years or more. If that is impractical, roughly assess the acorn-producing capacity of individual trees by observing production during a single year in which a good to excellent acorn crop occurs for one or more of the major species present. However, in the red oak group, many good producers may be overlooked in a single year because not all trees of those species may produce well in the same year. Criteria for identifying good producers are given by (table 1). The best time to rank trees in the oak-hickory region is from August 10 to 25, before acorn predators begin to eat or cache many acorns. Acorns are best observed with binoculars on bright days when they are silhouetted against the sky.

| Table 1. - A ranking of acorn production for individual trees* | ||

| Ranking | White Oak | Red Oak |

(Average number of acorns per bunch*) |

||

| Excellent | 18+ | 24+ |

| Good | 12-17 | 16-23 |

| Fair | 6-11 | 8-15 |

| Poor | Less than 5 | Less than 8 |

*Note that in any one year, excellent producers may not reach their potential because of unfavorable environmental factors.

**Based on the terminal 24 inches of healthy branches in the upper one-third of the crown.

2. During thinning, retain a mixture of oak species to minimize the impact of the large year-to-year fluctuation in acorn production in any one species.

3. Thin around the identified acorn producers to expose their crowns to full light on all sides. This facilitates crown expansion and increases branch density. Branch density increases acorn production per unit of crown area because of the increase in numbers (density) of acorn-bearing branches. Among the potential acorn producers, dominant and co-dominant trees will be the most efficient producers. Area-wide thinning is not necessary because only 20 or fewer good seed producers are likely to occur per acre even in pure oak stands. But because these seed producers typically will be dominant and co-dominant trees, they may account for proportionately more basal area and stocking than their numbers alone indicate.

4. Increase or decrease the rotation (or in uneven age management, maximum tree diameter) to include the tree diameter of maximum acorn production of the predominant species in each stand. For example, production in northern red oak peaks when tree d.b.h. reaches 20 inches and then it declines in larger trees (fig. 1). In contrast, white oak production is maximized at about 26 inches. Many other species, however, do not exhibit well-defined diameter-related peaks in production, at least within the diameter ranges that have been reported. Large, senescent trees are usually poor acorn producers.