The 17-Year Cicada Emergence is Wrapped up: Now what?

Cicada screams may be dying down for another 17-years, but there are still some lingering effects on the ecosystem from these insects. Periodical cicadas (aka 17-year cicadas) feed underground for most of their lives drinking sap from tree roots. Once every 17 years they emerge en masse, climb up trees, sing, mate, and lay their eggs on the tips of tree branches. This cycle is completely natural and has a long history in written and oral records. Cicadas are not harmful to humans, provide a feast for wildlife, and mostly only cause cosmetic injury to trees.

Cicada Biology

To understand the impact of 17-year cicadas (Brood X) on the forest, you first need to understand their lifecycle. These cicadas spend most of their life underground in their nymphal stage (juvenile stage) feeding on tree roots. They drink xylem from the roots using their straw-like mouthparts. There is little evidence that the nymphs do any serious damage to trees during this period. Most native trees are adapted to the cicadas and studies have found little to no reduction in their growth from this feeding. During this life stage, cicadas may burrow in the soil but rarely travel more than 1 meter.

Once they reach their 17th year, the nymphs will crawl closer to the surface of the soil and form tunnels often with mud “chimneys” on top. They wait there until the conditions are just right (64 degrees F). When they emerge, they look for a sturdy vertical surface to crawl up and will cling to it while they shed their skin. This stage is the most vulnerable part of the cicada’s life. If they don’t find a good location to molt or if they get knocked off before their skin has hardened, they can be seriously damaged.

Adult 17-year cicadas live for about a month and spend most of that time looking for a mate. The loud buzzing noise commonly associated with them is their courtship song. Once they’ve mated, the female cicadas begin laying their eggs in twigs of deciduous trees. The structure they use to lay their eggs, the ovipositor, is like a long needle. The cicada uses it to pierce the bark of the tree and place her eggs into the stem. In about 6-8 weeks the eggs hatch and the nymphs drop to the ground to begin the cycle again.

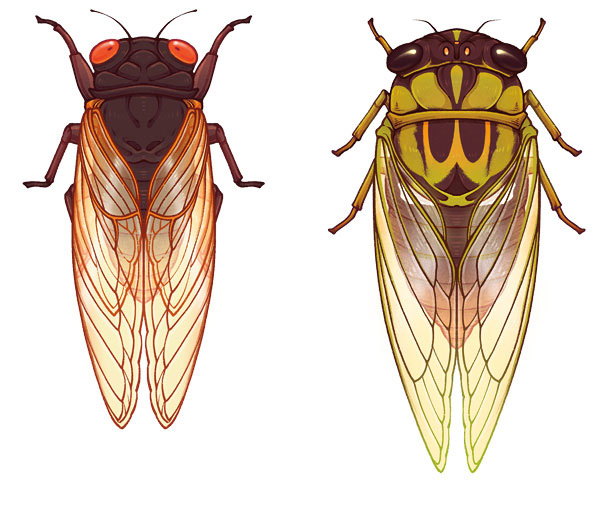

Cicada Identification Figure 1: A comparison of the 17-year cicadas (left) and the annual cicadas (right). Image by Lianne Pflug.

Figure 1: A comparison of the 17-year cicadas (left) and the annual cicadas (right). Image by Lianne Pflug.

If you think you’ve found a 17-year cicada after the end of July, don’t worry. It’s probably not another mass emergence. Instead, you’ve likely found a look-a-like of the 17-year cicadas. Cicadas tend to have sturdy, thick bodies with mostly clear wings that are longer than their bodies. Annual and 17-year cicadas are most commonly confused with each other. There are three main species of 17-year cicada in Indiana and about 16 species of annual and 13-year cicadas. 17-year cicadas are distinctive from the annual cicadas in that their bodies are a dark, nearly black brown with amber highlights on their wing veins, and red eyes (figure 1). Annual cicadas have green and black bodies and are a little bigger than 17-year cicadas (figure 1). To see a full comparison of the most common insects that are confused with 17-year cicadas download our Cicadas-and-Their-Look-A-Likes reference from Purdue’s cicada website (https://extension.entm.purdue.edu/cicadas/).

Impact on plants, animals, and what to do about it

The emergence of the 17-year cicadas is generally regarded as having either a net neutral or positive impact on the ecosystem. When these insects crawl to the surface, they are effectively moving a massive volume of nutrients in the form of their bodies from underground to above ground. This change has wide ripple effects throughout the forest community.

Impact on animals

Any animal that eats insects had quite the feast this spring. Cicadas are incredibly abundant in some areas, slow, and functionally defenseless against predators. The addition of these insects to animals diets has far reaching consequences for predators and for their normal prey. The emergence of 17-year cicadas is often tied to higher numbers of and heavier weights of many species of animals in the year following an emergence. On the upside, this means that wild turkeys tend to be more numerous and fatter in the fall. On the downside, there tend to be more mice and rats. In both cases, the animals are able to eat their fill more consistently and with less energy expended foraging than in normal years. In addition, prey animals get some relief from predators that would otherwise eat them. For example, there may be an increase in the number of some birds because animals (e.g. raccoons) that would normally eat their eggs satiate their hunger with the more easily accessible cicadas.

Impact on plants Figure 2: Egg laying damage caused by 17-year cicadas. Note the distinctive hole connected by a split in the twig. Image by John Ghent.

Figure 2: Egg laying damage caused by 17-year cicadas. Note the distinctive hole connected by a split in the twig. Image by John Ghent.

Most of the damage done to trees by cicadas is caused by their egg laying (oviposition). 17-year cicadas will feed and lay their eggs on more than 270 species of deciduous woody plants. Cicada females prefer to lay their eggs in branches that are about 3/16 to 1/2 inch in diameter. Cicadas lay eggs by stabbing their ovipositor into tree bark which can create scars in the bark. Egg laying sites look like a row of small nail holes often with a crack or indentation between the holes (figure 2). There may be more than one line of holes if multiple cicadas lay their eggs in a single twig. If enough cicadas lay eggs in the same place, it can kill the twig. This damage often looks worrying (figure 3), but isn’t a serious problem for well-established, healthy trees. These dead twigs can be trimmed off either by the landowner or by a professional service.

Cicadas can have some positive benefits to trees as well. When the 17-year cicadas die, their bodies drop to the forest floor and begin to rot. Their death introduces a source of nutrients into the soil at an unusual time of year. There are studies that suggest that it may give a small boost in growth to trees and smaller plants in the understory. Additionally, the tunnels cicada nymphs dig in the soil may help with aeration. However, it’s important to note that these positive benefits may be undetectable if another stress like drought is present.

Summary Figure 3: An example of the typical damage caused by cicada egg laying. Although it looks serious, this damage is unlikely to cause any long-term harm to the tree. Image by Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources-Forestry.

Figure 3: An example of the typical damage caused by cicada egg laying. Although it looks serious, this damage is unlikely to cause any long-term harm to the tree. Image by Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources-Forestry.

Cicadas, despite their dramatic entrance every 17-years, have little negative effect on the forest ecosystem and, in many cases, provided an extra burst of nutrients for plants and animals alike at the start of the growing season. In most cases, the small amount of damage they cause can be removed or ignored with no harm to the tree. Further information on management can be found on the Purdue Cicada website (https://extension.entm.purdue.edu/cicadas/).

Elizabeth Barnes is an Exotic Forest Pest Educator with the Department of Entomology at Purdue University.